A stereoscope card of Vienna’s Ringstraße from 1898

Robert Musil’s unfinished modernist epic The Man Without Qualities is one of those literary ‘masterpieces’ of the 20th century that people mean to read one day but never get around to skimming for more than a chapter or two. I’ve seen the Knopf two volume boxed-set on bookshelves for years–I mean, when people still have bookshelves; the apartments I go to lately have a lot of Ottolenghi cookbooks, and that’s about it–but the novel is untouched, an aspiration or a thwarted ambition rather than book to freely live with. I can understand why the novel and all its heady, high-modernist ironies can seem like a lot to take on; but I can tell you as someone who has taken on Musil’s The Man Without Qualities (well, a lot of The Man Without Qualities, anyway) over and over again, it’s a ridiculously fun reading experience, and it’s about something very fundamental: how to live.

In this way, The Man Without Qualities has more in common with Sheila Heti’s How Should a Person Be?, or Karl Ove Knausgaard’s My Struggle, than it does with other ‘difficult’ modernist novels from the 20th Century that people aspire to read one day, like James Joyce’s Ulysses.

I’m going to try something new this winter break and offer a special 5-week course on Musil’s The Man Without Qualities. I’ve taught the book before at different levels, but this will be a condensed “deep” read of Volume One of the Sophie Wilkins/Burton Pike translation for Knopf from 1996, which includes the first two volumes of the novel Musil published in his lifetime, ‘A Sort of Introduction’ and ‘Pseudo Reality Prevails.’ That second phrase alone: ‘pseudo reality prevails.’ I hear it in my ear every time I see Marjorie Taylor Greene in my news feed, or when Ye pulls on his black hood for another interview with a white conspiracy profiteer.

The class will use a free and easy-to-navigate platform for communication, sharing files, and keeping up with the weekly reading assignments : Google Classroom. [UPDATE: after experimenting with a few different platforms, I have started a private Substack for the class. Once you join, I’ll send an invitation.] We’ll also meet on Zoom three times, and I’ll be preparing a few audio lectures on specialized subject areas. Since the novel is so deliberately set in the Vienna of the Ringstraße, the Secession movement and its Art Nouveau totality, the thriving literary culture of Cafe Griensteidl and other haunts, we’ll touch on some of the novel’s cultural influences, including:

Freud and the dreamwork of early psychoanalysis.

The literary feuilleton and its masters: Peter Altenberg, Joseph Roth.

The aphorisms and political satire of Kark Kraus.

The Secession Building in Vienna and Gustav Klimt’s Beethoven Frieze.

Atonal music, esp. Alban Berg and his opera “Wozzeck.”

Architect Adolf Loos and his modernist reaction against ornament–we’ll look closely at his highly problematic design (unbuilt) of a home in Paris for Josephine Baker, featuring an indoor swimming pool with glass sides, to showcase her swimming body.

A digital rendering of Loos’s design for an interior swimming pool for Josephine Baker, by Stephen Atkinson and Farès el-Dahdah.

I’ve also commissioned new translations of some phenomenally unsettling short prose pieces by the feminist experimental writer known only as “El Hor” or “El Ha,” who had a meteorically brief career–her identity has never been uncovered by scholars. She even signed her publishing contracts with her pseudonyms.

This background material will be presented in compelling ways, and any additional reading, looking, or listening will be purely optional. This course is designed to help guide your own reading of The Man Without Qualities, to ease your journey through Vol.1 and open up the vanished world of the novel.

There are just two required books:

Musil’s first novel, The Confusions of Young Törless (translated by Mike Mitchell), Oxford World’s Classics, ISBN 978-0199669400 ($13).

The Man Without Qualities, Vol. 1: A Sort of Introduction and Pseudo Reality Prevails (translated by Sophie Wilkins and Burton Pike), Vintage, ISBN 978-0679767879 ($25).

It’s essential that you purchase these editions and not the alternate translations that are floating around. You’ll have to order these books on your own before the class starts, preferably from your local independent bookseller or through Bookshop.

The course will begin with a ‘soft launch’ on January 9, 2023, for those who’d like to start the New Year by reading Musil’s first novel, Young Törless. Let’s call this first week a ‘sort of introduction,’ too. Registration for the class will remain open during this optional week.

Then the rest of the class will begin with five weekly installments dedicated to The Man Without Qualities, from January 16 until February 20.

I will be scheduling the Zoom meetings closer to the start date.

The cost for the class is $250, payable by Venmo, Zelle or personal check before January 9 or January 16 (depending when you begin). There is a discount for senior citizens and for students. I can also offer you a discount if you’re facing economic stress. I am keeping the cost of this class low so that it’s accessible to as many readers as possible.

If you have any questions or you’d like to register, send me an email at [email protected]. I can also be reached on my Facebook page.

And spread the word if you know a reader who might be interested.

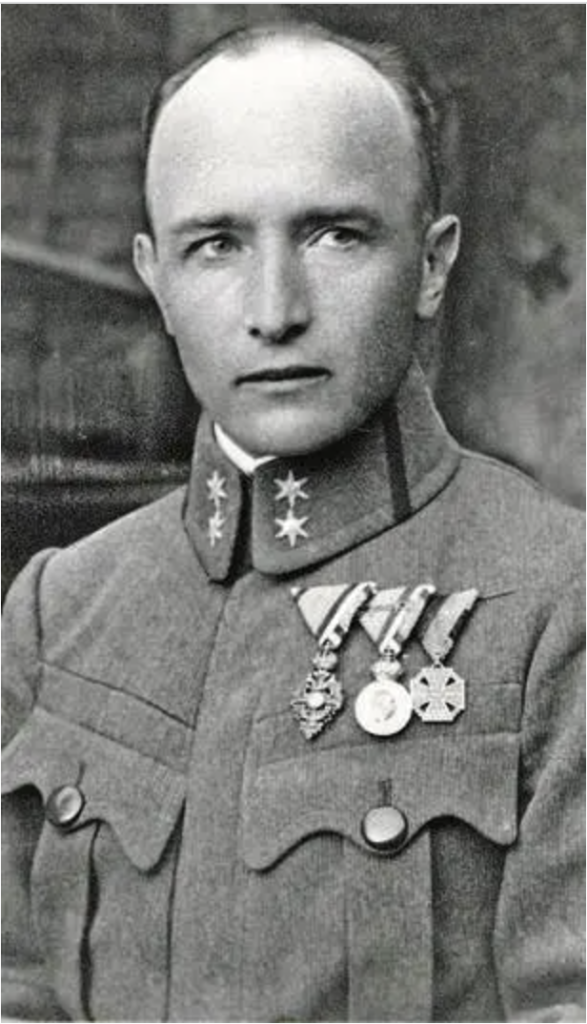

Robert Musil in 1918, Literaturmuseum Klagenfurt