I never could get used to the name: Twitter. That “twit” dressed up for the office in a second syllable, taking a word we already knew—Twitter, v., a condition of twittering or tremulous excitement (from eager desire, fear, etc.); a state of agitation; a flutter, a tremble—and re-branding it for a social media platform where everyone becomes an avatar, churning out individual news feeds for their followers in 140-character microbursts that beg for our attention, each and every one.

It’s a natural enough impulse to find a nice high perch in the trees and start broadcasting. I mean, isn’t this what the birds do? The name, though—Twitter—was an obstacle for me from the start, in part because it was so patently stupid, but also because I recognized that it was stupid in just the right way and would probably make the people who coined it billionaires. I’d seen this principle at work during the Tech Boom of the late 90s, albeit in nascent form—take a pre-existing idea, like home-delivery service, slap a goofy name on it that could only have originated in a conference room with a whiteboard (kozmo.com!), offer the product online for free, then wait for the V.C. money to start falling from the sky.

It was thrilling, in a way, to watch whole swaths of New York get remade by Silicon Alley before the tech bubble started to deflate, to see the packs of start-up rascals with their exalted titles, younger than me by less than a decade but already a generation apart, palming their mysterious devices on the subway, bouncing with energy in their $150 retro sneakers, free of the self-consciousness and fear that I’d always understood to be necessary for survival in the city.

“How did the world change so quickly?” I used to wonder from my seat nearby, holding a notebook open in my lap, full of tiny scribbles, or a paper copy of the Times before it shrank to its current size, which will never look right to me in proportion to the world. “Why is what they have so fucking valuable?”

I’ll admit it: I did a lot of muttering then, both aloud and under my breath, about the stupidification of New York by dot com capital, and whenever I was in a mood I used to howl at the Yahoo billboard on Houston Street, or give a surreptitious kick to the kozmo.com drop box at Ciao Bella on Mott while I was walking out with my fancy ice cream. It was professional envy, plain and simple, one small revolt against the change in natural order that was already underway—and still hasn’t stopped. Print would be dethroned by the glowing screen; authority was no longer earned, but freely available to anyone who seized it; forget about reflection, care, “craft,” meaning, value, and all the other slow-twitch talents I’d spent my life trying to master, the age of fast-twitch thinking had arrived, and the click was now king.

It’s not as simple as that, of course. I have learned that outcomes, at least when it comes to technology, are not as Manichean as we believe them to be in the moment. I’ll take my media intake today—and that includes the links I click on thanks to the far worldlier people I follow on Twitter and Facebook—over what was available to me in the year 2000 any day of the week. It’s no contest.

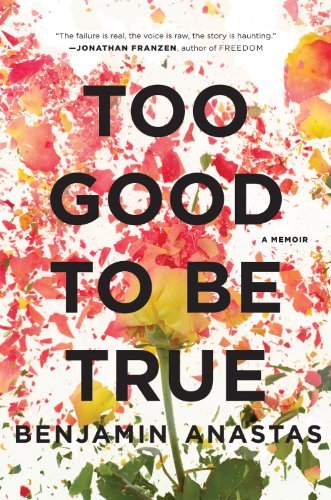

And yet. I’m leaving Twitter. I’ve had enough. Just writing those last two sentences makes me feel better than a guy with sideburns describing his first Cronut on Yelp. My stay in Twitter Village was brief: 1 year, 4 months and 22 days. I’ll freely admit that I never really got the hang of it, never felt the buzz of a perfectly composed tweet, the thrill of communion with a multitude of fellow travelers united by a hashtag. I came. I saw. And now I’ve had it. No más.

I’ve written my last tweet.

I’ll be posting an essay here on my experience with Twitter and why I think the social media presence typically recommended to writers when they’re publishing a book is a tremendous waste of time.

What follows is Part One: “I Wanna Dance with Somebody.”

I joined Twitter on February 2, 2012 (#dayone) because of a conversation I had over lunch at Schnipper’s on 8th Avenue with my friend A., a novelist who I’ve known since we were at graduate school together in the early 90s. Back then, you were a tech-savvy writer if you carried enough change in your pockets to check your answering machine messages from a payphone, or brought a Sony Discman when you went running on the treadmill. I used to communicate with my literary agent at the time by letter; I saved my work on 5 ¼ inch floppy disks and printed it out on sheets of dot-matrix paper that I tore by hand; I didn’t own my own fax machine yet, but I did have a pretty deep and sincere attachment to my off-brand P.C. Aside from personal computing, which made editing and printing manuscripts a lot easier, the business of being a writer hadn’t changed much since Flannery O’Connor was hammering away at her typewriter at home in Milledgeville.

“Two pages a day!” the director of our M.F.A. program, Frank Conroy, used to bellow in workshop, a single crooked finger pointed up as if to teach us a lesson in the value of cognitive dissonance. “Two pages a day!” You did the work methodically; you stared and cursed and tore your hair out and tried to will the words to do your bidding; you stacked and ordered your pages until the book was done, and then you started writing it all over again from the beginning. That was the writer’s work, and it was a sacrament—a ritual handed down by the Gods of Good Clean Prose on onionskin paper. Everything else was publishing—imagine the word delivered with a weary sigh—and the only thing worse than publishing was working for a living.

Alone among the writers I knew who’d studied with Frank, A. had started blogging early on and continued to stay active. In the years between his published books the blog had given A. an outlet for ideas that wouldn’t easily fly with magazine editors, and a means to build an audience of readers. He spent a lot more time on Facebook than I did, and he had enough followers on Twitter to make him something of a guru in the literary world when it came to social media. When writers had a book coming out, they often sought him out for advice. Just like I was doing.

“If you don’t enjoy it,” he told me right off, “you’re wasting your time.”

“That makes sense.”

“Everyone will know you’re faking it.” He delivered this line with one eyebrow raised, like a character planting a clue in a Peter Lorre picture.

“They will?”

“Trust me.”

A. gave me a lot of other good advice that day—I hope I at least picked up the lunch tab; sorry, A., if I let you buy your own burger—but the biggest take-away for me, especially when it came to Twitter, is that you have to tweet because you want to instead of feeling like you have to because a publicist implied that it was necessary. When you publish a book these days, you’ll be encouraged to do three things: (1) build an author’s website (which generally costs between $2500 and $5000 of your own money); (2) create a Facebook fan page (this is free, but completely useless, unless you have an intern or a spouse who’ll post on it more or less constantly to take advantage of Facebook’s internal algorithms); (3) get on Twitter to build your new Gaiman-like following by any means necessary.

This is already much too long for a blog post, so I’m going to cut right to the chase. I spent the next week or so lurking around on Twitter with a dummy account to see what other writers were up to with their feeds, from a performance artist like Gary Shteyngart to the fiercely distilled aphorisms of Jenny Diski. Once I was better acquainted, or so I thought, with the Tweet as a formal exercise and what you could do with it, I dove right in.

The first few days were fine. I followed friends and they followed me back. I followed journalists I admired, and writers whose work I read, and lots of editors and publishing people who tweeted about the book business (I was working on an article at the time and this was a big help for my research).

On February 12th, or #dayeleven, I was doing some work at home with Twitter open on my web browser when I saw this Tweet from Salman Rushdie in my feed:

That’s strange, I thought. Whitney who? And why is Salman Rushdie thanking her on Twitter? I’d followed Rushdie out of idle curiosity on one of my first days, having given up on reading his work after Fury, which has to be one of the five worst novels about New York ever written. (It makes sense, I guess, when your view of the city originates at Indochine or from your regular table at the Waverly Inn.) Was he thanking the Whitney Museum for a favor? Or was I just missing something?

A few clicks and I found out the reason behind his tweet. Whitney Houston had died, found floating in the bathtub at her hotel suite in Beverly Hills. The news wasn’t particularly meaningful to me—I have a weird indifference to celebrity, even when I’m in the same room as a movie star—but it did feel completely wrong that I was hearing about Whitney Houston’s death from Salman Rushdie.

After his first tweet about Whitney’s death, Rushdie followed up with a tribute of his own:

It was too much to think about. I’d had my fill of Salman Rushdie on the death of Whitney Houston. It was too much! My mind lit upon on a series of images that got progressively more morbid: In the first, Salman was at his computer typing “I Wanna Dance with Somebody” into a Google search and waiting too eagerly for a response from the overloaded servers (“But wait,” Salman thinks, “should I post ‘How Will I Know?’ instead? ‘All the Man I Need’? That might add a nice touch of irony …”); then Salman had opened up the video for “I Wanna Dance with Somebody” and was watching it with a wistful smile on his face, one tear running down a powdered cheek; and last, Salman was shaking it to the song on the dance floor, somewhere small and packed in Manhattan, like the old Bungalow 8, his raven haired partner, much younger, beaming back at him with sweat glowing on her skin and laughing as she twirled.

“Salman!” she yelled over the music. “I didn’t know you could boogie down!”

I went about my day without dwelling on it too much. Twitter, of course, was all aflutter about Whitney Houston’s death, filling up with personal tributes, links to performances, jokes to test the boundaries of what was “too soon,” expressions of sadness and outrage—the collective wail that goes up from the village square whenever there’s a shared trauma to expunge or an injustice to protest. The whole thing made me feel uneasy. It seemed wrong, all of a sudden, to be privy to such an outpouring of emotion on Twitter; rather than an enlargement, a moment of shared empathy, it made everyone seem smaller, like mourners competing for attention at a public funeral. Or maybe the problem was me for not caring enough about Whitney Houston? For not bowing to force of history?

I tried to put it all out of my mind, but I couldn’t. Twitter had opened up a portal to unwanted intimacies with a literary celebrity, to unspeakable things on an imaginary dance floor, and that night I couldn’t sleep because I was implicated in the whole sorry business. I had joined Twitter, crossed over to the other side, joined the endless clamor coming over the hills from Twitter Village. Wasn’t it bad enough that I’d written a memoir? Did I really want to start live-tweeting my reactions to events that had no relation to me and links to songs on YouTube?

The next morning I woke up from a dissatisfying couple hours of sleep and lay on my back with my eyes wide open.

Thank you, Whitney.

“I can’t do this,” I said to ceiling.

The next installment of this essay will be “Lessons Learned.”

Should I share this on Twitter using Windows Phone 8 or on Google + with the Slate? Maybe I’ll just use the iPad and post it on Facebook. Ugh. Thanks for making me realize how much I hate myself.